Will Grant v. WWE stay in open court or go to arbitration?

An appeals court ruling in another case last year could have bearing on the lawsuit that accuses Vince McMahon of sex trafficking

Last week the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut formally allowed former WWE employee Janel Grant to update her lawsuit against Vince McMahon, John Laurinaitis, and WWE. The amended sex trafficking complaint adds new details and explicitly names individuals who were previously obscured with pseudonyms.

Before Grant’s allegations themselves can be litigated in open court, the judge must first decide whether the case will stay in federal court—as Grant wants—or if it will move to private arbitration, as all three defendants want. Moving the case to arbitration relies on a clause in the $3 million nondisclosure agreement that Grant and McMahon signed on January 28, 2022, which ostensibly requires all related disputes to be handled through binding arbitration—a private process conducted outside the public court system, often mediated by a retired judge.

While arbitration relieves courts from having to take on more cases, critics argue arbitration tends to favor powerful parties by limiting the ability to gather evidence, shielding the litigation from public view, and making it difficult to appeal.

There are a variety of issues the judge will likely consider when assessing whether to approve or deny the defendants motions to compel arbitration. Rather than trying to account for all of them, we’ll consider here one recent case, Olivieri v. Stifel, which may be relevant to Grant’s allegations.

The defendants are due to re-file their motions to compel arbitration by June 13. Grant will have an opportunity to request evidence related to the arbitration question and to submit a written opposition to the motions.

For reference, the full arbitration clause in the executed Grant-McMahon agreement reads:

In the event of any dispute arising under or out of this Agreement, its construction, interpretation, application, performance or breach, the parties agree to first attempt to resolve such disputes informally and prior to taking any formal legal action to resolve such disputes. In the event any such dispute cannot be resolved informally, all parties hereto agree that the sole and exclusive legal method to resolve any and all disputes and/or controversies is to commence binding arbitration under the Federal Arbitration Act pursuant to the procedures of the American Arbitration Association and to do so by sealed proceedings which preserve the confidential and private nature of this Agreement. The parties agree to discuss the venue for any such arbitration proceeding if and when such a dispute arises which cannot be informally resolved; but in the event the parties cannot agree on a venue then the exclusive venue for any arbitration proceeding shall be in Stamford, Connecticut. The prevailing party, as determined by the arbitration tribunal, shall be entitled to recover from the non-prevailing party all of its attorney's fees and costs. (3:24-cv-00090-SFR, ECF No. 85-3, Section X at 5)

Grant has raised public policies, like the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), which she argues are in her favor. The TVPA established serious consequences for perpetrators of trafficking and those who knowingly benefited from trafficking. But it doesn’t mention arbitration.

The Speak Out Act, passed on December 7, 2022—almost a year after the contract here was signed—limits the enforceability of nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) that would prevent a person from publicly discussing sexual assault or harassment.

The law isn’t retroactive, though, stating:

“This Act shall apply with respect to a claim that is filed under Federal, State, or Tribal law on or after the date of enactment of this Act” (Public Law No. 117-224, § 5).

That aside, the act says nothing about arbitration.

The Ending Forced Arbitration of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment Act (EFAA) is likely the only federal law that directly concerns arbitration in sexual misconduct cases. The act took effect on March 3, 2022—mere weeks after Grant’s NDA was finalized—and allows plaintiffs to choose to go to open court, even if they signed a contract with a mandatory arbitration clause.

But the EFAA isn’t retroactive either. The statute ends with a sentence similar to what’s in Speak Out.

“This Act, and the amendments made by this Act, shall apply with respect to any dispute or claim that arises or accrues on or after the date of enactment of this Act” (Public Law No. 117-90, § 3).

While the lawsuit describes several events that took place around the EFAA’s effective date, neither Grant’s complaint nor any other of her filings to date reference the law. However, she alleges the following.

On March 2, 2022, while Ms. Grant was away on a trip to Florida, McMahon called Ms. Grant to advised [sic] that it would probably be the last time she would hear from him and, if she needed anything, to contact Nick Khan or Brad Blum. Over the course of an approximately half hour call, McMahon lamented both his inability to focus on the upcoming WrestleMania and how his personal life had blown up over the past few weeks. Towards the end of their conversation, McMahon and Ms. Grant agreed to resume contact after WrestleMania. He also instructed Ms. Grant to continue having sexual relations with other men, including Brock Lesnar, in the meantime (3:24-cv-00090-SFR, ECF No. 117, ¶ 268, at 66).

Still, March 2 is literally the day before the EFAA was enacted. Then, in the next paragraph, with the EFAA having just been enacted on March 3, 2022, she claims:

On or around March 4, 2022, Lesnar messaged Ms. Grant that he was in New York. In line with McMahon’s orders, Ms. Grant texted Lesnar explicit pictures (ECF No. 117, ¶ 269, at 66).

On March 27, 2022, Lesnar reached out to Ms. Grant again. Ms. Grant understood that these back-to-back advances were an indication of McMahon’s continued control (ECF No. 117, ¶ 270, at 66).

WWE and McMahon have already anticipated this exact issue related to the EFAA in their earlier motions to compel arbitration even though Grant hasn’t raised the law to this point.

The defendants raise two main points.

Accrual: They say all of Grant’s claims accrued (became legally viable) before March 3, 2022, so the EFAA doesn’t apply.

Predispute agreement: They argue that the Grant-McMahon contract was a postdispute agreement. The EFAA covers only predispute agreements, not postdispute agreements.

WWE and McMahon both cite case law that says a claim accrues at the moment the alleged misconduct happens, thus giving a person a right to file a lawsuit.

To point (1), WWE’s attorneys argue that the events post-March 3, 2022, are after Grant is no longer employed with WWE, so they can’t apply to the company, and besides, those allegations “could not be severed and litigated separately from the pre-March 3, 2022 claims that unquestionably are outside the purview of the EFAA” (ECF No. 86-1, at 25).

On the issue of Grant’s alleged interactions with Brock Lesnar in March, McMahon’s attorneys stated: “The sparse allegations in the Complaint that postdate March 3, 2022, allege no actionable misconduct, and therefore do not alter the analysis” (ECF No. 85-1, at 30).

On point (2), WWE contends that because Grant was no longer employed at WWE by the time of the Lesnar texts, that WWE is free from the effects of the EFAA. Even if she was still employed at that time, WWE argues, “claims related to these post-Agreement allegations could not practically be litigated separately from, and in parallel with, the pre-Agreement claims that are subject to arbitration” (ECF No. 86-1, at 25), though WWE does not seem to have persuasive authority, let alone binding authority, to support that assertion.

McMahon aims to establish the second point, citing the text of the EFAA itself.

“The EFAA can invalidate only a ‘predispute arbitration agreement,’ defined by the EFAA as ‘any agreement to arbitrate a dispute that had not yet arisen at the time of the making of the agreement’” (ECF No. 85-1, at 30).

Neither WWE nor McMahon mentioned the alleged leaking of Grant’s name to the public in their earlier motions.

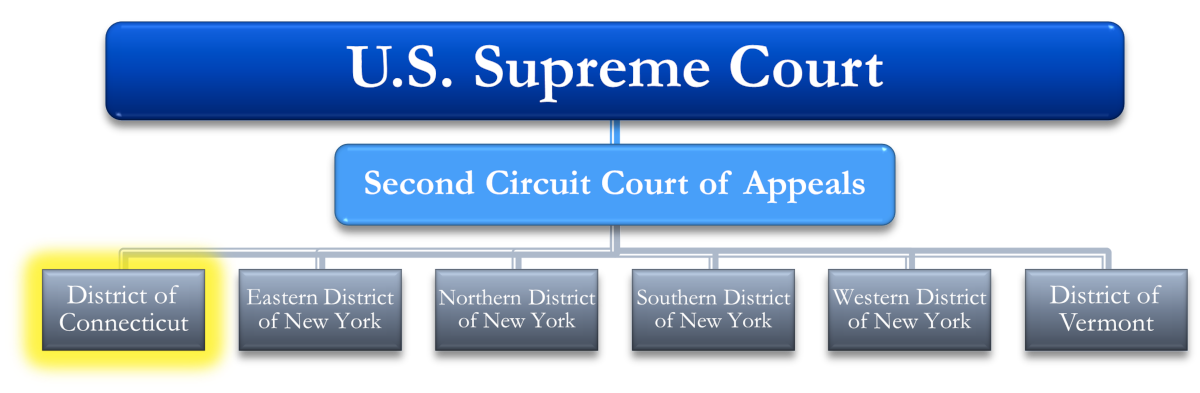

With the EFAA being a relatively new law, there may not be much precedent to establish how the act is interpreted. Both WWE and McMahon cite persuasive authority—cases from other U.S. District Courts—but they don’t cite more crucial binding authority, that is, case law from the Second Circuit Court of Appeals or the U.S. Supreme Court.

However, the Second Circuit’s ruling in Olivieri v. Stifel, decided in August 2024, sets binding precedent that may be relevant to this case.

Patricia Olivieri sued her employer, Stifel, and manager for sexual assault, harassment, and retaliation. Like Grant, she had signed an agreement requiring arbitration, though it was a pre-employment agreement. But like Grant, much of the alleged misconduct happened before March 3, 2022.

In fact, Olivieri’s case was sent to arbitration by a federal judge in the Eastern District of New York just weeks after the EFAA was enacted. Seemingly no party mentioned the new law. A few months later, Olivieri began the process to amend her complaint and cite the EFAA as the reason why she shouldn’t be forced into arbitration, arguing that she was still being retaliated against after March 3, 2022.

The lower court judge reversed her earlier ruling, finding that Olivieri’s claims accrued after March 3, and therefore, the arbitration clause was unenforceable under the EFAA—despite the defendants’ effort to compel arbitration.

Unsurprisingly, the defendants appealed, continuing to argue that the plaintiff’s claims post-EFAA accrue before the EFAA’s effective date.

Nonetheless, the Second Circuit upheld the District Court’s decision.

[T]he continuing course of conduct that underlies [Olivieri’s] retaliatory hostile environment claim persisted after the EFAA was enacted. Her claim thus accrued after the Effective Date, the EFAA applies in this case, and she was permitted to invalidate her arbitration agreement (23-658-cv, ECF 65-1, at 5).

The court applied the “continuing violation” doctrine, which allows a court to treat a series of related actions as one extended episode, as long as at least one part occurred during the law’s effective period.

The Second Circuit reasoned in Olivieri that if even part of the alleged misconduct accrued after March 3, 2022, and forms part of a single, continuing episode, the EFAA could bar enforcement of the arbitration clause.

Pursuant to the continuing violation doctrine, the statute of limitations for hostile work environment claims runs from the time of the last act in the continuing course of discriminatory or retaliatory conduct. (23-658-cv, ECF 65-1, at 5)

As discussed above, Grant describes text messages with Lesnar on March 4 and March 27, 2022. She alleges those events stemmed from McMahon’s previous instructions and continued influence.

Although McMahon’s attorneys characterize those allegations as “sparse” and not actionable, the court may assess whether they plausibly allege that coercion or retaliatory conduct tied to the broader sexual misconduct dispute continued beyond the EFAA’s effective date.

Also possibly relevant, Grant alleges retaliation continued beyond March. She says her identity was publicly leaked by someone within WWE to media member Brad Shepard on June 17, 2022, two days after the allegations against McMahon became public for the first time. Grant describes that as an “overt intimidation tactic” by WWE (ECF No. 117, ¶ 29 at 7). She connects this leak to McMahon’s prior promise of confidentiality and suggests it was intended to silence or retaliate against her.

If the court accepts that theory, the claim could fall within the EFAA’s scope as well, since Olivieri emphasized that post-March 3 retaliation tied to a sexual harassment or assault dispute can bring the entire case under the statute’s protection.

WWE and McMahon, however, may argue that Olivieri is different in important ways. In Olivieri, the plaintiff signed a pre-employment arbitration agreement, the exact category of “predispute arbitration agreement” the EFAA was designed to target. Grant, on the other hand, signed her agreement on January 28, 2022, as part of a post-employment settlement, which the defendants assert was intended to resolve an existing dispute, not anticipate a future one like in Olivieri. The defendants may cite the law’s definition of a “predispute arbitration agreement,” which covers only agreements made before a dispute has arisen, and contend that this doesn’t apply when the parties are settling known claims, like in the case of Grant, McMahon, and WWE.

Because Grant alleges some misconduct occurred after signing—including both McMahon’s final alleged assault (still pre-EFAA), supposed Lesnar texts and the alleged publicizing of her name (post-EFAA)—the arbitration clause might be interpreted as predispute for those events, if it was ever intended to cover future claims at all.

The defendants might also say that any conduct that occurred after March 3, 2022, doesn’t constitute actionable conduct, which would question Grant’s claim to harm with regard to her interactions that month with Lesnar, even if accepted as true.

As to these defendants, Lesnar is not even a party to this lawsuit, after all. And here WWE may again point out that Grant, who says she gave the company notice in February, was no longer employed there by the time of the March interactions with Lesnar.

McMahon wasn’t directly involved in any of those events, they may contend, and therefore those aren’t allegations against him.

But Grant would likely allege that the Lesnar texts post-EFAA were the result of McMahon’s continued sex trafficking of her. She could further contend the trafficking was part of a continuing pattern of conduct, potentially connected to McMahon’s relationship with Lesnar, as part of a contract negotiation or an exchange related to Lesnar’s services to WWE. Those allegations, if accepted, could implicate both the company and McMahon.

Further, Grant characterizes the later disclosure of her name as an act of intimidation, which she attributes to WWE, though she makes this claim based only on information and belief. At the time, Grant was not a public figure. Other reporters who may have known her identity likely withheld it, recognizing her as a potential victim of misconduct. WWE and McMahon may deny any involvement in publicizing her name. Shepard himself attributed the information to “a source in #WWE”, which connects the source to the company, though, not necessarily to someone acting on its behalf, such as an officer of the company or member of the media relations department.

Even if the court accepts that some post-March 3 conduct is relevant under the EFAA, the defendants might still argue that even if the EFAA potentially invalidates the arbitration clause, the question of whether this case should be in arbitration or not has already been delegated in the text of the clause to the arbitrator, not the judge. They could lean on the Rent-A-Center v. Jackson Supreme Court case, as they have in other arguments, which gives arbitrators the authority to decide such “threshold” or “gateway” issues. Allowing this, though, would seem to defeat the EFAA’s purpose, which was specifically to invalidate predispute arbitration clauses.

However Judge Sarah F. Russell may interpret these issues, the Olivieri decision affirmed the notion that claims can accrue on the date alleged misconduct or retaliation occurs, such as the interactions with Lesnar that she says were part of McMahon’s trafficking of her or WWE’s alleged retaliation against her in purportedly publicizing her name.

If Grant’s allegations are construed by Russell as part of an ongoing pattern of coercion or retaliation—one that includes events after March 3, as Grant seems to be alleging—then the court may find that the EFAA applies, even though her arbitration clause was part of a post-employment agreement.

But if the court finds the post-March 3 events too isolated, speculative, or unrelated to the original dispute, it could still enforce the arbitration clause.

Note: I’m not a lawyer. This article is only a journalistic analysis, and not an authoritative legal opinion and it's definitely not legal advice. I relied on legal definitions from universities and relevant case law from the courts via public resources like CourtListener, Justia, and Google Scholar. To remove any doubt: while I routinely contact representatives of the parties in Grant v. WWE to request comments when reporting factual news stories, I did not discuss the legal analysis explored in this article with any party, representative, or person with a direct interest in this case before publishing this. I'm definitely not an attorney but if you are (or if you're not and you just have thoughtful comments), I'd be glad to hear from you.